INTRODUCTION

We are all capable of describing the visible world. But sometimes things are more than what we see. We can describe our surrounding, as reality, to someone or we can visualize it. There are many ways of visualizing reality. Drawings, especially, are very helpful in understanding how we think about reality and how we translate our thoughts into an image. For many centuries, scientists and theoreticians have presented their research and discoveries through drawings. Although they used different styles of representations depending on the technical development of the time, nowadays, digital tools provide new opportunities to visualize, catalog, and interpret reality.

This study is based on understanding how we see reality, how we interpret it, and to evaluate which processes allow these interpretations to be realized. From these issues, many questions can be posed: How much is a drawing linked to reality? What can a drawing represent exactly? How do we interprete what we see as a drawing? What is the process behind this interpretation and how can we visualize it? To summarize, we can formulate our research question as follows:

How can we visualize different processes of interpreting reality through drawing by hand and digitally?

In order to analyze this, an object , representative of reality, was chosen as a focus for the entire study. The chosen object should be organic and capable of remaining unchanged throughout the entire investigation. For these reasons, a seashell was selected.

Experiments have been conducted by drawing the shell using a variety of tools depending on the need and by illustrating various aspects of the object itself. Through the experiments, we will explore aspects of the shell, choose which tools are better suited for particular tasks, and create combinations of drawings (called ”hybrids” in this study) to reveal more about the object. We will also explore how the combination of analogue and digital techniques bring new ways of representations of reality.

As our starting point, we will discuss why drawing is important as an interpretation of the reality. Second, we will look at the history of the representation of shells from early centuries until today. And finally, we will analyze different processes of interpreting reality by categorizing the drawings and looking at the role the body plays in the drawing process.

I. WHY DRAWING?

When

we

draw

something

,

we

go

enter

a

world

with

endless

possibilities.

We

must

grasp

things

with

our

hands

in

order

to

represent

our

thoughts.

Drawing

is

considered

a

trace

of

the

thinking

process.

It

is

“an

invented

scene

of

the

imagination”1.

Through

drawing,

it

is

possible

to

translate,

document,

record

and

analyse

the

world

we

inhabit.

It informs

the

viewer

about

the

visible

and

invisible

world.

But

what

does

it

say

exactly,

and

how

is

it

possible

to represent

the

invisible?

1. Drawing as a process teller

The act of drawing reveals a lot about how the drawing was produced as well as many details about the process. The viewer can read the drawing by bringing his unique experiences and perception into the study of each drawing he sees. The drawing becomes not only a trace of the artist’s idea but also of the process. In the lines, we can see decision and indecision, if it was made quickly, slowly, angrily, with force, with care, randomly or gently. These are all different ways we can interpret our world.

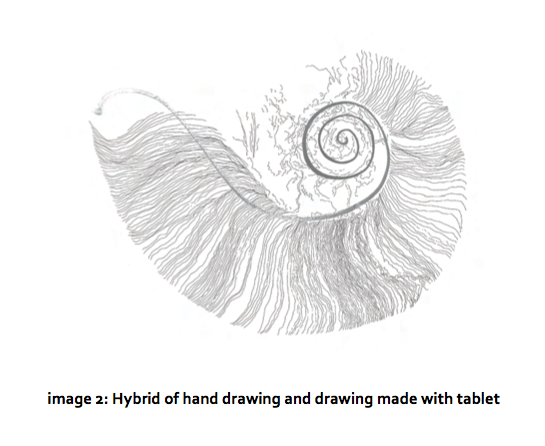

Image 2 shows how a drawing can inform us about the process. The representation of the spiral was created using analogue and digital tools. In order to represent texture, the lines on the shell were drawn carefully with a tablet, aiding the ability to erase any undesirable lines. Although the texture was created digitally, the influence of the hand gesture is still visible in the shaking lines. In contrast to the texture, the form of the spiral was created by pen in a free, quick, and continous way. This allows the form even more visible. This hybrid is a good example of how we can understand a process through a drawing.

Drawing is an important way of vizualization when it is fitting to a purpose. It can be used as a tool of exploration. Searching through drawing is an old technique, and nowadays, it is used in many fields in order to question, study, and communicate a specific problem. For engineers, town and country planners, and designers of all conditions, drawing is a way of generating new knowledge and sharing it. If we consider that “Drawing is discovery” 2 as John Berger said, then we can consider it the pathway to visualizing the unknown.

Searching through drawing is a dialogue between what we see and what we know; While drawing, the research process develops through seeing and interpreting, skills which are influenced from our knowledge and cultural background. Any idea visualized, ultimately spawns more ideas. The act of searching and exploring should lead one understanding.

Furthermore, through drawing, we can express a feeling, a thought, or anything not yet exisiting in reality. of the apparent truth. This is how the invisible becomes visible. Engineers, envisioning the not‐yet‐made, use pencils and pixels as they search for the clearest representation of their ideas. Next, they share their drawings with colleagues and those responsable for the manufacturing process. In this, research through drawing is communicated to others.

In this project, the chosen object, a shell, has been drawn. One direction involved imagining how the inside of the shell, the invisible part, would look if visible. Through various analyses, sketches and hypotheses, a final decision was reached. This is another example of searching through drawing (images 3a‐3b).

First, the shell has been measured and its outlines have been drawn with the correct proportions. Then, after searching other shells’ X‐rays, an attempt at visualizing a similar structure was made. It is interesting to compare how the final drawing is similar to the X‐ray results taken at then end of the project (image 3c‐3d).

II. HISTORY OF THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SHELL

1. Early examples

One

of

the

earliest

representations

of

the

shell

was

made

by

Athanasius

Kircher,

in

Mundus Subterraneus which was published in 1665. Kircher, developed important conventions for the visual representation of the Earth; an important subject of study for seventeenth century’s theoreticians. In Kircher’s representations, the Earth was depicted as a shell‐shaped mass or a fossil shell dome with the human body placed in the center. (images 4a‐4b).

Another example of shell representation was created by Antoine‐Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville. Searching for rare shells, he spent a life time developing a system of classification and publishing books on the subject. His book, Conchiliology/Shellsor, or Shells‐Muscheln‐Coquillages, consists of attractive illustrations by Antoine‐Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville of fossil shells found in 1780. He spread the knowledge and discoveries which he made. In his drawings, he showed the great varieties of shell structures and the harmonies of the innumerable shapes between them (images 5a‐5b). D’Argenville attempts to bring order to nature by organizing all the shells he found according to size, form, and color.

It is also interesting to examine the works of the 17th century. During this time, it was common for still life works of art to depict natural objects (food, flowers, plants, rocks, or shells) or man‐made (drinking glasses, books, vases, jewelry, coins, pipes, and so on) in an artificial setting. Image 6 shows a painting by Jan Davidsz, a precious shell cup, which dominates the composition in the diagonal arrangement. We can see how the shell becomes an object of daily life with its unique form.

During the 18th century, painters, sculptors, architects and even candlestick makers all followed the curve of the shell. The style was called rococo, from the French word rocaille, meaning fancy work in rocks and shells. This royal style allowed many ornaments, with organic a symmetrical or spiral forms — symbols of growth — to flourish. In architecture, Stiftsbezirk Kathedrale in Saint‐Gallen is an excellent example of the use of spiral structure in architecture. The spiral form was repeatedly used on the columns and ceiling as an ornamental element (image 7a‐7b).

2. New techniques

For centuries, biologists and mathematicians have explored techniques for describing shell geometry in simple terms. These approaches help to draw the shell as a two‐ dimensional object embedded in three‐dimensional space. Today’s technology allows opportunities for new ways of representation: it is possible to create a model of a three‐ dimensional shell by using parameters and calculations. It is then possible to draw a shell with a cutting plane or multiple ones. These images show more than the external shape as they inform the viewer about its interior form.

In addition, there are other techniques based on complex computer‐generated modelling. (image 8a‐8b). A variety of materials processing techniques can be used. Furthermore, new software applications are capable of creating images through the interpretation of mathematical formulas.

III. PROCESSES OF INTERPRETING REALITY

1. Tools

In

visual

interpretation,

the

media

we

choose

is

already

a

part

of

the

interpretation.

Nowadays,

there

is

a

wide

array

of

possibilities

open

to

the

artist.

On

the

one

hand,

traditional

methods

and

tools

continue

to

dominate:

Artists

draw

using

pencil,

pen,

charcoal,

ink

and

brush,

pastels,

and

colored

pencils,

however

digital

media

is

becoming

increasingly

more

important;

As

in

all

areas

of

modern

life,

the

computer

is

moving

into

the

realm

of

illustration,

and

as

a

tool

it

is

only

as

successful

and

stimulating

as

the

artist

using

it.

Many

who

mix

their

media

have

begun

combining

any

number

of

the

above

techniques.

In

our

study,

analogue

and

digital

tools

have

been

used

according

to

the

need.

a. Analogue

Pencil is a fundamental tool when researching through drawing and in the search for the right proportions of a form (image 3a). As it is possible to erase what has been drawn and redraw on the same surface, one can make multiple attempts without any fear. In this study, drawings completed with pencil are self‐explanatory. Therefore, the idea is very clear in the image.

In contrast, the use of pen is highly successful for sketching. As sketches suggest spontaneity and subjectivity the thought is visualized immediately on the paper. The sketch is the trace of the first impression of an idea, similar to doodling. Sketches do not have to be finished. Frank Gehry, in his architectural sketches, uses continual, free and playful lines, without trying to be objective and faithful to the representation of a building. His aim is not to describe or illustrate, but to seek and evoke (image 9a‐9b).

As with watercolor, with ink and brush, one can draw lines in colour, these lines are hard to direct. They flow almost randomly and the artist has only limited control over them. A major part of the watercolor line simply emerges. In his writing, Walter Benjamin mentions that watercolour, is in this respect, a medium in which painting and drawing meet. 1 This is also valid for ink.

b. Digital

Digital media is an important tool for many reasons. The roles that drawing can assume has broadened considerably with technological developments in online communication and software.

Vector graphics are excellent for excluding unnecessary detail. This is especially useful for information graphics or line art. This technique is also very successful in repeting lines or forms, or calculating.

The visual quality of digital images depends upon the pixels and their density. The number of pixels in an image, its resolution, is a key determinant. The development of tools such as graphic tablets help to produce digital drawings and to acquire some of the characteristics of an analogue image.

As a code based program, Processing is an interesting programming language which helps to create images through numbers and formulas. Many other new digital manipulation software and processing languages can be exploited. However, at times the images created through processing can be too complex in parallel to the complexity of the data we have generated.

2. Aspects and hybrids

When we discuss the visualization of reality, we shoud consider its characteristics: form, texture, inside, light, and shadow. For each attribute we are going to examine three important examples.

a. Texture and form

There are diverse possibilities which can be created from the combination of form and texture drawings. This is the most extended category of them all. There are many things to discover about form and the texture of an object, because these are the most evident characteristics of the object.

The process can be quite different depending on the tools used. For example, ink and brush are very useful when we want to describe the form of the shell with simple strokes. The fluent curves of the shell can be represented with quick brush strokes on the paper. When too much water is used, traces of the ink appear when the paper dries. These traces form colored waves which appear remarkably similar to shapes on the real object (image 10). This is an interesting coincidence from which a hypothesis can be formed: the shell’s texture must be created through the movement of the water over the surface. Likewise, the form visualized by ink and brush, when combined with the texture represented by repetitive vectoral lines, gives a very close impression of this natural effect on the shell’s real texture.

Image 11 is a result of a process in which form and texture were combined. The form of the shell was drawn by using a pencil, which creates colour values helping the viewer’s eye to move easily and quickly accross the form. In order to represent the texture, the lines on the shell were freely drawn with the digital tablet allowing for the ability to easily erase any undesireable results. Although the texture was created digitally, the influence of the hand remains visible in the shaking lines. The hybrid, as a final image, is deprived of being voluminous, only a little with the pencil drawing. Nevertheless, lines inform us about the roughness of its surface. Even if the representation is a combination of hand and digital drawing, as the tablet is conserving the hand control, the result appears made by hand.

Here, the results of the process is well‐matched, however there are other examples in which contrast has been established.

The quick movement given by the brush and the calculated, repeated and rotated lines form a contrast between them (image 12).

b. Exterior and Interior Form

Image 13 shows the process in which the pencil was used to create form in a simplified way while the inside structure was represented as drawing through code. Here, a programming language was used to visualize an interpretation of reality. The data based programs help to create complex images which would be difficult to produce by hand.

Another process is developed by combining exterior form and interior structure (image 14). Here, we can see how the proportions of the interior can be carefully drawn with the use of a vector program. This technique allows for precision in contrast to the exterior form which was drawn with quickly with pen. Although the form was developed freely, in an abstract and simplified way, the vector illustration of the shell still plays a role in the visualization without the need for a cover.

Another shell interpretation was created by brush to reflect the form of the shell and while the inside structure was produced as a carefully drawn vector illustration (image 15). The combination seems as if the spiral was covered with the brush strokes resting on a different layer.

c. Form and Light/Shadow

The combination of form versus light, and shadow is limited because it includes the study of the representation of light and shadow. Our investigations using processing thus far have been concerned with the texture and interior representation. The codes written here are not suitable for investigating light and shadow. However, there are other tools used for this purpose.

One successful combination is that of ink/brush and pixel drawing (image 16). With the brush, the paper was completly painted black; only the form of the shell appears white. The brush strokes are dominant on the paper. The second layer depicts the light reflected off the surface of the shell. This layer has been prepared digitally in Painter, a pixel based program. By choosing the ink tool, it appears handmade, creating a harmony between two techniques.

Another hybrid is ink and vector drawing (image 17). The water based ink drawing was created by using large quantities of ink to preserve the voluminous aspect of the shell and shadows. In contrast, the form was drawn digitally with vectors in such a way that we get perceive the idea of a shell. The combination is far from being an accurate interpretation of the real object and the vectoral representation of the form seems like another cover over the shell itself (shown with ink). If we loose attributes such as texture and form, the hybrid illustration becomes too general. The danger here is that it can be read as an interpretation of any organic object defined by light and shadow.

The most interesting hybrid for this combination is image 18. The process begins with a vector drawing of the outline of the object. Thus we get acheive a simple form for the shell. The shadows on and around the object have been drawn with pen. The representation is very quick and dynamic. When we combine these two vector forms the shadows transform the image into a three dimensional object. This is a simple but effective representation of form through light and shadow.

d. Texture and interior form

As ink and brush are very successful in depicting movements and curves, especially when done quickly, the interior form was created with fast, gestural brush strokes (image 19). In contrast, the shell has repeating lines on its surface which form a slightly rough texture. This pattern becomes interesting as a complement to the gestural brush strokes. Because accuracy is on e of the main characteristics of the computer, the texture was drawn through vectors by repeating a single line at regular intervals.. The combination shows, on the one hand, the elegant flowing spirals of the center overlayed with a series of precise lines lending a the three‐dimensional quality to the form of the shell. On the other hand, it contains a contrast between the automatic repetition of the lines and the quick interpretation of the interior form.

Another process of interpreting the shell’s interior form and its texture is the hybrid between pen and the coding language known as, processing (image 20). The pen is used to represent the exterior texture of the shell. The pen drawing is created through dynamic lines without any specific direction. The inside structure is illustrated by using a specific code. The image created is based on small dots moving and turning which, when both drawings are combined, emphasizes the dynamism of the form. The hybrid is then in harmony in itself.

Image 21 is created using pencil to represent the inside form, and the tablet, to depict the exterior texture of the shell. While the hand‐drawn pencil lines seem very carefully executed, the represenation of the texture appears much more similar to a free hand drawing despite being created digitally. Like the image 19, the texture seems transparent; alluding to the interior form of the shell.

e. Texture and Light/Shadow

The

first

hybrid

is

very

different

than

the

others

because

of

its

process

(image

22).

The image is based on fingerprints produced with ink, then scanned and manipulated. The idea originates from observing the texture of the skin. As identity, and the light dark colors of the fingerprint can be seen as light and shadow. The manipulation is then executed with a pixel based program in order to achieve an image similar to the real shell.

The next image, image 23, shows the texture drawn by processing and the shadows created through pen. The texture is presented as lines in the form of waves on the white paper. The addition of the interior part of the shell creates an invisible material under the texture and on top of the shadow. This effect emphasizes the lines drawn by codes and connects them to the object in the real world.

Another example is the combination of light represented with pencil and texture formed by a vector illustration (image 24). In this hybrid we can only see the light on the object and the lines are not visible because of the shadows of the dark background made by pencil.

f.

Interior

form

and

light / shadow

The hybrid in image 25 illuminates another type of process. The light and shadow were created with ink and brush. The quantity of water put on the paper plays an important role on the light and dark part of the image. Here, the effect created is three‐dimensional. At the same time, processing was used to represent the inside structure of the shell showing the dynamic movement and rotation of the spirals. The benefit of drawing through codes is that it allows one to render complex images with very small details, something extremely difficult to produce by hand. In contrast, the ink reveals the inside structure and creates the effect of transparency, a visualization we do not see in reality. The hybrid is successful as the shell appears transparent, allowing us to see the inside structure.

Another interesting process occurs when we use the calculated spiral and the shadow of the shell together (image 26). The inside structure becomes the shell itself and we can see it from the shadow it makes : the shadow does not take the form of a spiral but instead, that of the exterior form of the shell. This is a different interpretation of the reality.

A similar example is the spiral drawn with the light and shadow on the dark background (image 27). Here, the spiral becomes very difficult to see which makes the combination invisible.

3. Hand / eye connection in the process of interpreting reality

In different processes of drawing, the body, especially hand, plays a big role in drawing. As Valéry says in his book called Degas, Danse, Dessin 1, “There is a big difference between seeing something without pencil in the hand and seeing it by drawing. Or even, these two things are very different form each other. The object which we think is very familiar to us can become very different to us when we draw it. We understand that we have ignored it. That we haven’t really seen it. There is a transformation from visual drawing to manual drawing.“ When we interprete reality through drawing, we do not realize that this transformation occurs. We concentrate on representing what we see. We analyze the object, we break and mesure it with our eyes. We act like it was the first time we were seeing the object.

As for Derrida, the process of drawing has some kind of blindness. He thinks that while drawing, the artist behaves as if he was blind; he also says that drawing itself is also blind. He calls drawing as an intransive activity which means that “ our attention focuses on the representation of the world‐ as activity”. To understand the relation between hand and eye, an experience was made in the beginning and at the end of the project. The shell was drawn as a blind. Images 28a‐28b are interesting to compare how much the eye hand connection had an influence to our perception of the shell along the study. We can see that the first drawings done (image 28a) before the study look like a rough mass whereas the latest drawings are finely drawn by using short and careful lines (image 28b). The object seems to be studied piece by piece, due to the observation and practice by hand along the project.

The essence of drawing is in the gesture involved. When Roland Barthes talks about the american artist Cy Twombly’s drawings, he says that it looks like he produced his work with his left hand (image 29). In Barthes’ word, left‐handedness eliminates any association with techniques and Twombly explores the possibilities inherent in hand motion and breakes the rules imposed on the hand.

In this project, some of the processes of drawing of the shell have been recorded. This helps to observe our hands and the gestures we make through the tool we use. In digital as much as in traditional tools, our gestures differ. When we use a pen, for example, the hand gestures are energetic and fast, which make the lines fluent and powerful. While using ink and brush, the hand acts more carefully because one touch can change the whole image especially when we use too much water. Even if the hand tries to have the control, a very different result can appear with the quantity of ink, water, brush and paper we use: we can talk about an accidental aspect of the process which the hand overlooks. On the other hand, when we use the digital media, our fingers use s shortcuts with an authomatism. Then we can say that the digital language has to be learned like we learn how to use traditional tools. There are digital languages that artists, which introduce the computer programming within the context of drawing. Visual elements such as dot, line, and field are combined with variable numbers to generate images. Processing is a good example to talk about the programming language. Sometimes by writing codes, it is possible to have endless varieties of complex images. We write codes and the computer select images.

CONCLUSION

When we draw something, we go into a world with endless possibilities of interpretations. An object which we think we are very familiar can be a source of many studies on form, texture, invisible form and light / shadow. Elegant flowing spirals with brush strokes, or, invisible energetic interior movements with codes, covered by fluent and quick forms with pen, repetitive lines with vectoral lines, accidental water traces with ink and water, lights and shadows with pixels are just a few ways of interpreting reality. The shell, as a production of nature, is a good example to study different processes of interpreting reality with drawing considered as a trace of an activity.

All depends on how we perceive the objects around us, how much we are capable of controlling our hand gestures and which tools we use. This study can be a basis for many questions. It is then interesting to wait and see how much the varieties of interpreting reality will be extended in parallel to the development of technology and how it affects the extent to which people will allow their perception of reality to be changed.